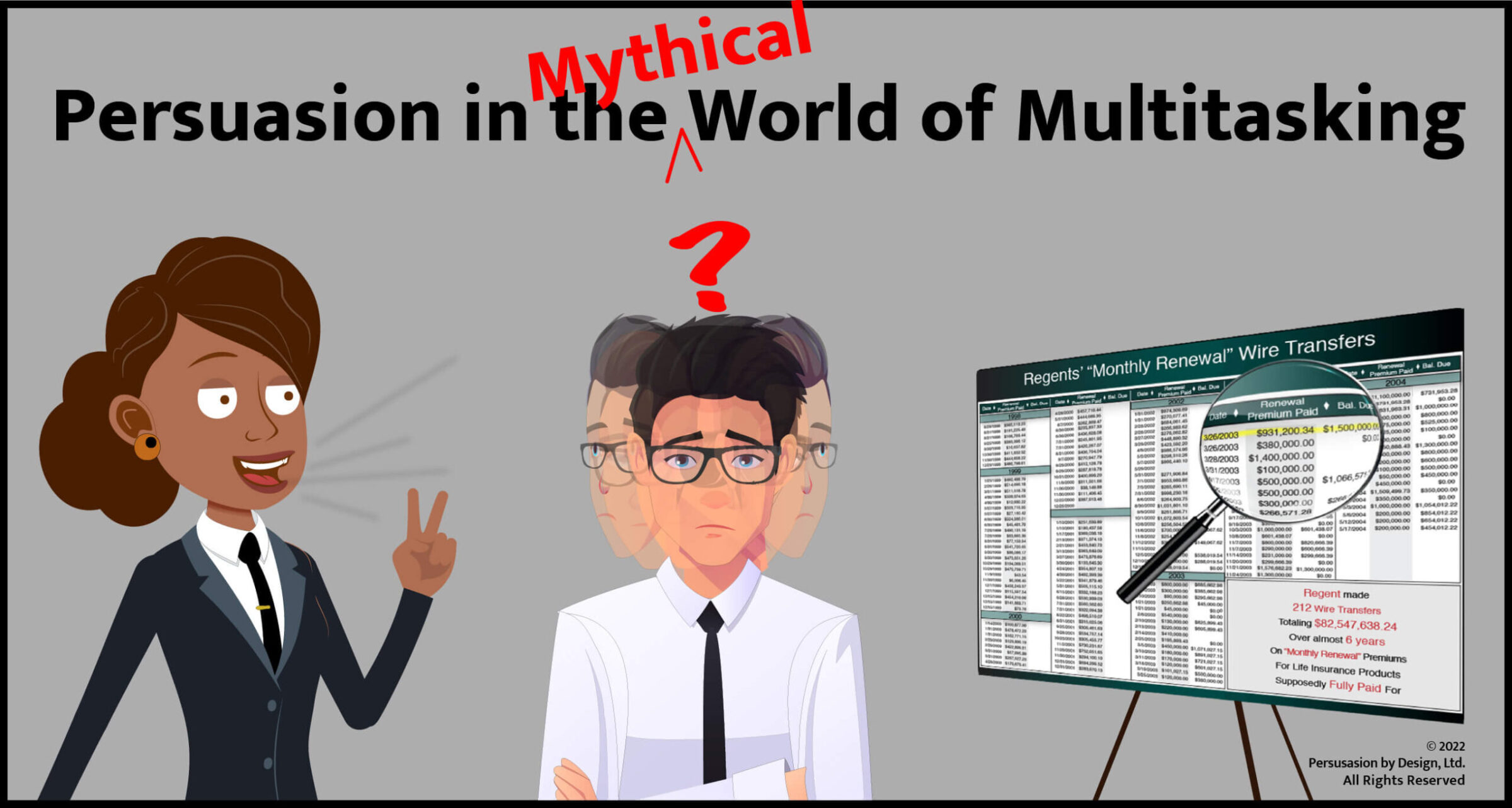

The Multitasking Myth

A human brain, presented with multiple, non-autonomous cognitive tasks, must process those tasks serially, not in parallel, meaning it must switch from one to the other and back again, often in milliseconds. Neuroscientists, cognitive psychiatrists, and others have studied the impact for decades: when “multi-tasking,” each task (such as viewing something or listening to someone) receives less cognitive attention, audience comprehension decreases, subject matter interest lessens, and the ability to retrieve information later is curtailed (the “HORRIBLES”). See, e.g., The Myths of the Digital Native and the Multitasker, Kirschner & De Bruyckere, 67 Teaching & Teacher Educ. 135 (2017)

The Lawyer’s Nightmare, i.e., The List of Horribles

Apply that science to the juror suddenly shown a full timeline—beginning to end. The juror’s reaction is predicted by the science. She reads ahead through the complement of boxes trying to discern their meaning and how they relate to what he has learned about the case so far.

Meanwhile, however, a lawyer speaks on the first event, and the second, and the ones that follow. Since the juror’s brain (like everyone’s) is incapable of processing both streams of information simultaneously, the juror’s attention bounces back and forth, giving rise to the List of Horribles (reduced attention, comprehension, interest, and memory). While obviously not a desired reaction to attorney presentations, the Horribles revisit courtrooms day after day, year after year, relentlessly subverting persuasiveness within a profession rooted in persuasion. This need not be the norm.

The Solution—Sequenced Demonstratives

Sequenced Demonstratives—demonstratives presented (i.e., built) through a series of cumulative layers—are integral to Persuasion by Design’s visual narrative approach. We use them, and use them often, for a simple reason: they persuade better. We’ve experienced their power firsthand while trying cases. And, now, as demonstrative designers, we’ve assisted a host of clients to realize the sequencing advantage themselves.

For example, in a breach of duty of loyalty / noncompete case, sequenced demonstratives worked especially well to focus attention on the defendants’ secret and adversarial actions while still employed by the plaintiff:

The ability of sequenced demonstratives to materially impact a case is firmly rooted in a host of (inter-related) cognitive processes: cognitive load; perceptual and processing fluency; many different heuristics, such as the picture superiority effect, the generation effect, and confirmation bias; and the list goes on.

The power of designing to these cognitive processes is seen in this contract breach case. Unique contractual circumstances required us to establish that the owner knew of the rampant fraud in his organization. Numerous employee-witnesses confirmed the fraud (each switched to red in the demo).

To see other examples of PxD’s demonstratives, please see our Portfolio.

Powerful Demo Presentations in Three Steps

Sequencing works best to avoid the Horribles when a presenter follows three simple steps:

1. Verbally PRIME the juror on what they should expect with the next event (thereby creating, for the juror, an analytic framework you have developed);

2. After advancing a slide to the new event, PAUSE and SILENTLY allow the jury the opportunity to review and consider the new element without multitasking interference and the concomitant List of Horribles; and, only then,

3. DISCUSS the event, which in large part should REINFORCE conclusions the juror has already made for herself having been led down the path you’ve made through the priming and the visual construct.

If you, too, are fascinated with the intersection of cognitive principles and legal persuasion (or, really, any type of persuasion), we’d love to hear from you.

And if you’re interested in learning how Persuasion by Design can meaningfully strengthen your case through visuals, just reach out.